How Has Ukraine Been Using its New Swedish AWACS?

Ukraine’s new airborne radar puts additional pressure on the Russian air-component, complicating the mission planner’s calculus: fewer safe corridors, less time on target, and increased risk.

Imagine you’re a Russian fighter pilot, flying in the western sector over Ukraine. You’re convinced your stealth tricks are holding up, maybe your radar is masked, perhaps you’re mid-altitude, hugging terrain, confident.

Then all of a sudden your radar-warning receiver lights up like a bingo hall on pay-day in Moscow. That signal comes not from a ground radar, not from a low-flying drone, but from a Swedish-donated twin-prop turboprop high above, casting its gaze hundreds of kilometers out.

That’s the moment when the modern airborne radar of Saab 340 AEW&C, also known in Swedish service as the ASC 890, enters the fight for Ukraine.

What is the ASC 890

The ASC 890 is essentially a conversion of the Saab 340 regional airliner… yes, the kind that once hauled business travelers and crying toddlers. In simplified terms: Saab pulled the seats, rewired the cabin, added a massive “radar bar” (the Erieye active electronically scanned array) on top of the fuselage, and turned the aircraft into an airborne early-warning and control (AEW&C) platform.

Detection range is the ASC 890’s headline number.

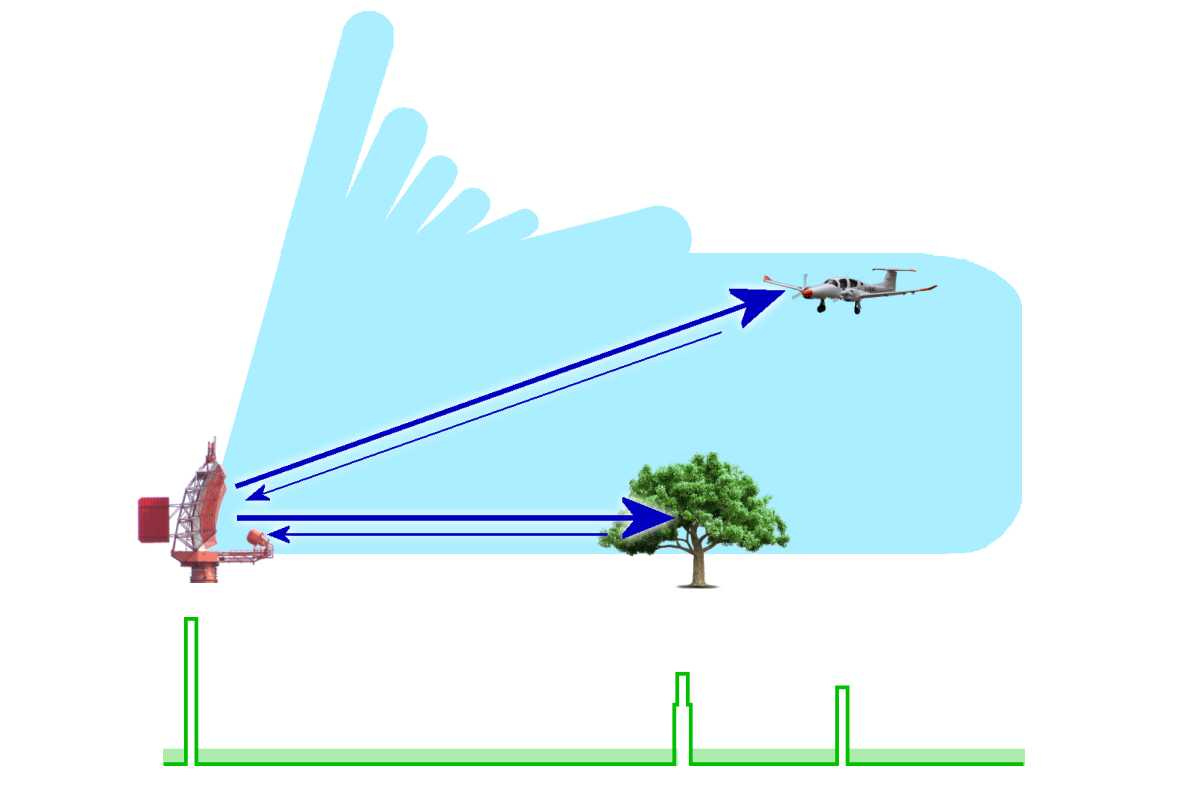

From typical operating altitudes the Erieye radar can pick up fighter-size targets roughly 300–400 kilometers away, though the exact figure bends with altitude, signature, and terrain clutter. In practice that means the plane can see far past the horizon of Ukraine’s ground radars and spot contacts well before they appear on ground nets.

It can also detect the things that used to sneak up on defenders: low-flying cruise missiles and small, terrain-hugging drones.

Ground radars lose track when terrain masks a flight path or an enemy deliberately skims tree line and ridges; ground clutter is a bitch.

The airborne radar sits above that clutter and gives Kyiv a chance to react before the threat is a fait accompli.

Finally, the ASC 890 is useful only insofar as it talks to shooters. Its value multiplies when its tracks stream into command-and-control nodes and into fighter and SAM systems in real time.

That feed turns raw detection into tasking orders, shortens decision cycles, and lets Ukraine vector interceptors or cue SAM batteries with far more lead time than ground sensors alone could provide.

In late May 2024, the Swedish government announced a major military aid package to Ukraine (~€1.16 billion) which included two ASC 890 aircraft.

By donating such an advanced system, Sweden is sending a clear strategic message about its view of Ukraine’s place in modern warfare.

Stockholm is treating Kyiv not as a recipient of spare equipment, but as a genuine partner in high-end air defense. The ASC 890 is not a throwaway asset, it is a complex, high-value piece of technology that only nations with mature command and control infrastructures can truly exploit.

By transferring it, Sweden is acknowledging that Ukraine has reached that level of sophistication.