Saab’s Dragon: The J35 Draken That Taught the World How to Fly Sideways

The Swedish Draken was built like a post-apocalyptic survivalist’s dream

I may have been a former infantryman, but my heart belongs to airpower. Which is probably why I left the Army after six years and joined the Air Force. So, indulge me in this deep dive into a lesser-known Swedish interceptor called the J35 Draken.

After all, this mythical beast laid the groundwork for another mythical modern marvel… the Gripen.

Birth of the Dragon

In the 1950s, while the rest of Europe was still trying to glue fins on leftover propeller planes, Sweden decided to build something that looked like it came from Flash Gordon. The Saab J35 Draken looked like it had overshot the timeline completely.

Born in the crucible of Cold War paranoia, the Draken (“Dragon”) was Sweden’s answer to a problem no one else was brave enough to solve: how to intercept Soviet bombers at Mach 2 and do it from highways.

Yep, highways. The Swedes didn’t have sprawling bases like NATO, and they figured those would be the first things nuked anyway. So, they wanted fighters that could take off from rural roads, let the pilot take a leak behind a pine tree, and get back into the fight before the Soviets could even refuel.

Saab’s engineers, equal parts genius and lunatic, accepted the challenge: design a supersonic interceptor that could hit Mach 2, land on a farm road, and still make it home for dinner.

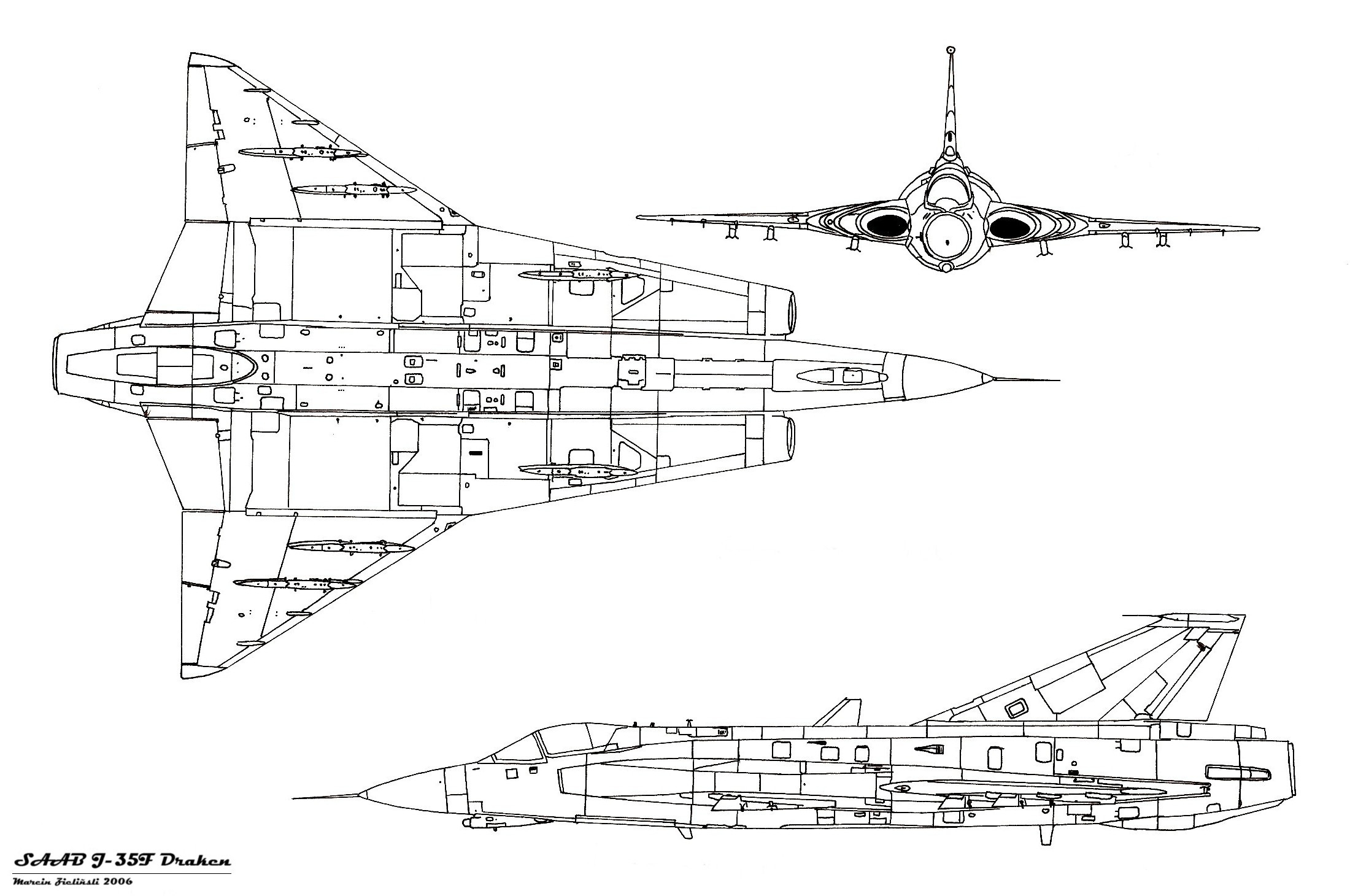

The Double Delta That Shouldn’t Have Worked

Saab’s engineers could have played it safe. They could’ve copied an F-100 Super Sabre or bolted on a tail like everyone else. But this was Sweden in the 1950s, a country that looked at the laws of aerodynamics and said, “Let’s see how much we can push them.”

The double-delta wing was the result of that mischief.

Instead of one consistent sweep angle, the Draken’s wing had two: a sharply swept inner section for high-speed flight and a shallower outer section for control at low speeds.

The idea was simple in theory and terrifying in practice. At Mach 2, the inner wing kept the aircraft stable and slick through the air. When the Draken slowed down for landing, the outer wing took over, providing lift and control so it didn’t drop out of the sky like a brick.

No one had ever flown a full-scale fighter with this configuration before. Wind tunnel data offered hints, not guarantees. Every engineer knew that one bad assumption about airflow separation or vortex lift could turn the project into a taxpayer-funded crater. Still, Saab pressed ahead, part national pride, part Nordic stubbornness.

The results were astonishing.

The Draken’s double-delta produced powerful leading-edge vortices that clung to the wing even at extreme angles of attack. In other words, when other aircraft were begging for mercy at high pitch, the Draken was still flying.

That same vortex lift, discovered by accident, later inspired advanced wing designs on jets like the F-16 and Rafale.

Even the airframe’s strength bordered on absurd. Its wing root had to handle both high-speed compressive forces and low-speed flex, something most designs treated as mutually exclusive.

Saab’s solution was an internal structure so overbuilt it could have survived a nuclear blast. It gave the Draken an almost comical durability. Pilots joked that you could land it on gravel, sweep the bugs off, and fly it again before Fika.

Author’s note: Fika is my new Swedish obsession… It’s basically a social ritual of pausing work to socialize with coffee or tea and a sweet treat, like a pastry.

The double-delta also gave Sweden something priceless: independence. It meant they didn’t need to buy fighters from the US or Soviet Union. They’d built their own supersonic aircraft from scratch, with no blueprints, no imported design language, and no backup plan if it failed.

And yet it worked beautifully, defiantly, and decades ahead of its time.

What began as an experiment in geometry ended as a masterclass in controlled chaos, and a warning to the rest of the aviation world that Swedish innovation was already flying past.

The First Jet to Pull a Cobra, By Accident

Every now and then, aviation progress takes a wrong turn and stumbles into brilliance. The Saab J35 Draken’s discovery of the Cobra maneuver is one of those moments where physics and luck shared a smoke break.

During early test flights, Swedish pilots noticed something peculiar. When the Draken pitched its nose up at a high angle of attack, it didn’t snap into a violent stall like every textbook said it should.

Instead, it paused, nose pointed skyward, hanging in the air for a fraction of a second before calmly recovering. That wasn’t supposed to happen. In aerodynamics, that’s like watching a penguin hover midair… it defied everything pilots had been taught.

The engineers called it “kort parad,” or short parry. To them, it was just one more weird quirk of their double-delta experiment. But in practice, they’d stumbled upon one of the most dramatic and tactically valuable maneuvers in aviation history.