Sweden’s Kreuger-100 Drone Hunter Just Rewrote the Rules of War

Every infantry battalion is now an air defense node.

Friends, I write a lot… At least six articles (and two videos) a week. However, I’m having a difficult time keeping up with the flood of technological innovation coming out of Sweden over the last six months. Forget Patriots—this Swedish startup just changed drone defense forever.

Thanks to Ukraine’s ingenuity, small drones are now part of every battlefield. Whether you’re in Ukraine, Gaza, or the Red Sea, you're either flying drones or fending them off.

Unfortunately, most current counter-drone systems look like someone strapped $500,000 worth of sensors to a laser pointer and hoped for the best.

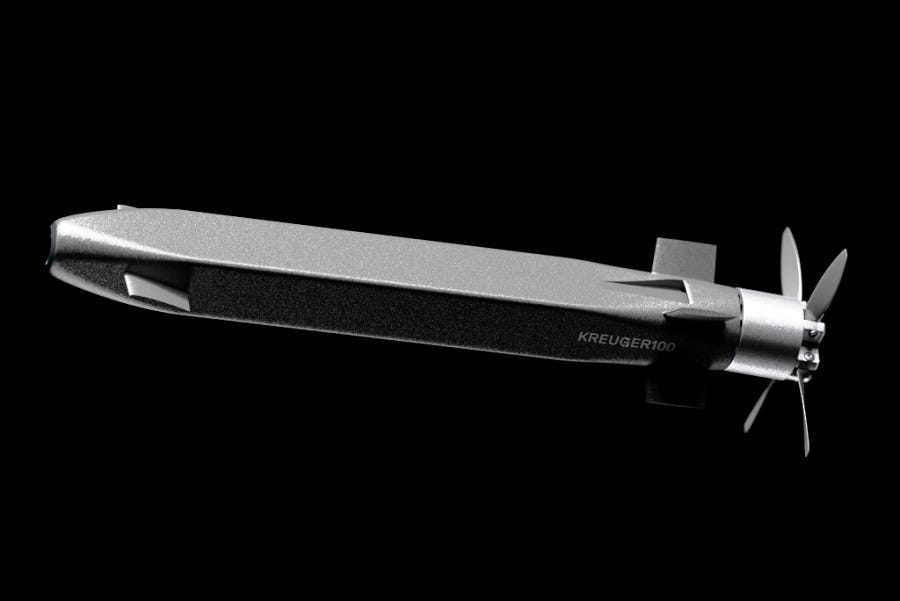

Enter yet another tech marvel from Sweden: the Kreuger 100. A stripped-down, software-driven interceptor that’s less F-35 and more Ikea flat-pack missile.

That’s not an insult. That’s the future.

Launched by Nordic Air Defense (NAD), a Stockholm startup that clearly got tired of watching Europe buy defense tech from across the Atlantic, the Kreuger 100 was designed from the ground up to be cheap, scalable, and fast to deploy.

The fact that it’s battery-powered, manually launched, and guided by algorithms rather than expensive sensors makes it as disruptive as it is unassuming.

And here’s the kicker: It’s already turning heads across Europe.

Software Eats the Sky: Inside the Kreuger 100

What sets the Kreuger 100 apart isn’t just what’s inside but what’s missing.

In the traditional world of air defense, interceptors come bloated with cost-heavy payloads: radar transceivers, laser rangefinders, gimbaled optics, complex gyroscopic stabilization, and propulsion systems that look like they were ripped from Cold War cruise missiles.

The Kreuger 100 throws that model out the window and replaces it with a radical, minimalist architecture where the real brainpower lives not in hardware but in code.

At the heart of this interceptor is a machine-learning-based flight control algorithm that adapts to environmental variables in real time: wind, angle of attack, target evasion maneuvers, and even thermal distortion caused by cluttered urban landscapes.

Instead of reacting like a heat-seeking missile on rails, the Kreuger 100 behaves more like a predator drone with a nervous system. It doesn’t just follow, it predicts. It calculates an interception course based on probabilistic modeling of the drone’s behavior, a kind of anticipatory flight path generation that gives it a split-second edge in a knife fight in the sky.

And unlike traditional systems locked into proprietary software ecosystems, the Kreuger 100 is designed to run on modular, updateable codebases.

That means when a new drone threat emerges, say, a smaller, faster loitering munition or a decoy swarm, the Kreuger’s software can be updated without touching the hardware. Think of it like your smartphone downloading a firmware update to recognize new threats. In war, that adaptability is gold.

Its infrared tracking system, while simple by Western standards, is fully integrated into this software layer. Rather than relying on heavy stabilization and high-end optics to isolate a heat signature, the Kreuger uses digital signal processing and software-based noise filtering to lock onto targets even with low contrast or amidst thermal clutter.

It’s not the most powerful eye in the sky, but it’s smart enough to see through fog, rain, or smoke and still make the shot.

Finally, the lack of traditional actuators or gimbaled fins doesn’t make it less precise, it makes it less vulnerable.

With fewer moving parts to fail, the Kreuger 100 can be launched hundreds of times with only software-based diagnostics to ensure flight readiness. It doesn’t just run lean, it runs persistent. A battery-powered hunter that can sit ready in silence until triggered, updated overnight, and deployed en masse without a logistics tail that stretches for kilometers.

This is what makes the Kreuger 100 dangerous. It’s not just a drone killer, it’s a software platform with wings. And that opens the door to future capabilities beyond interception: drone jamming, loitering surveillance, decoy behavior, or even kinetic strike roles.

When software defines the platform, the possibilities expand exponentially.

In short, the Kreuger 100 doesn’t match legacy interceptors feature-for-feature. It leapfrogs them by reducing complexity, cutting costs, and moving the brain from silicon to code. The result is a nimble, adaptable air defense solution that behaves more like a swarm AI than a missile.

And in this age of algorithmic warfare, that’s exactly what makes it so disruptive.

The Kreuger 100’s development reads like a startup myth in the making.

The project began after conversations with Swedish physicists at the FOI (Sweden’s defense research agency) revealed that onboard hardware could be replaced with real-time software control and aerodynamic design tweaks. What followed was a rapid prototyping sprint powered by simulations, secret field tests, and three pending patents.

With €1.2 million in funding from private backers like SNÖ Ventures and Volvo’s former CFO, the team moved out of stealth mode in late 2024. Unlike traditional defense companies, NAD isn’t just making a product, it’s building a category.

Their ambitions point toward a full suite of autonomous, modular defense tools spanning air, sea, and subsea.

Tactical Implications: When Mass Deployment Becomes a Strategy

In the drone age, quantity has a quality all its own, and the Kreuger 100 is built to exploit that reality.

My recent article on Germany’s drone wall proposal illustrates that point.

Unlike legacy interceptors that are deployed sparingly due to price tags that resemble small warships, the Kreuger 100 flips the economics of defense.

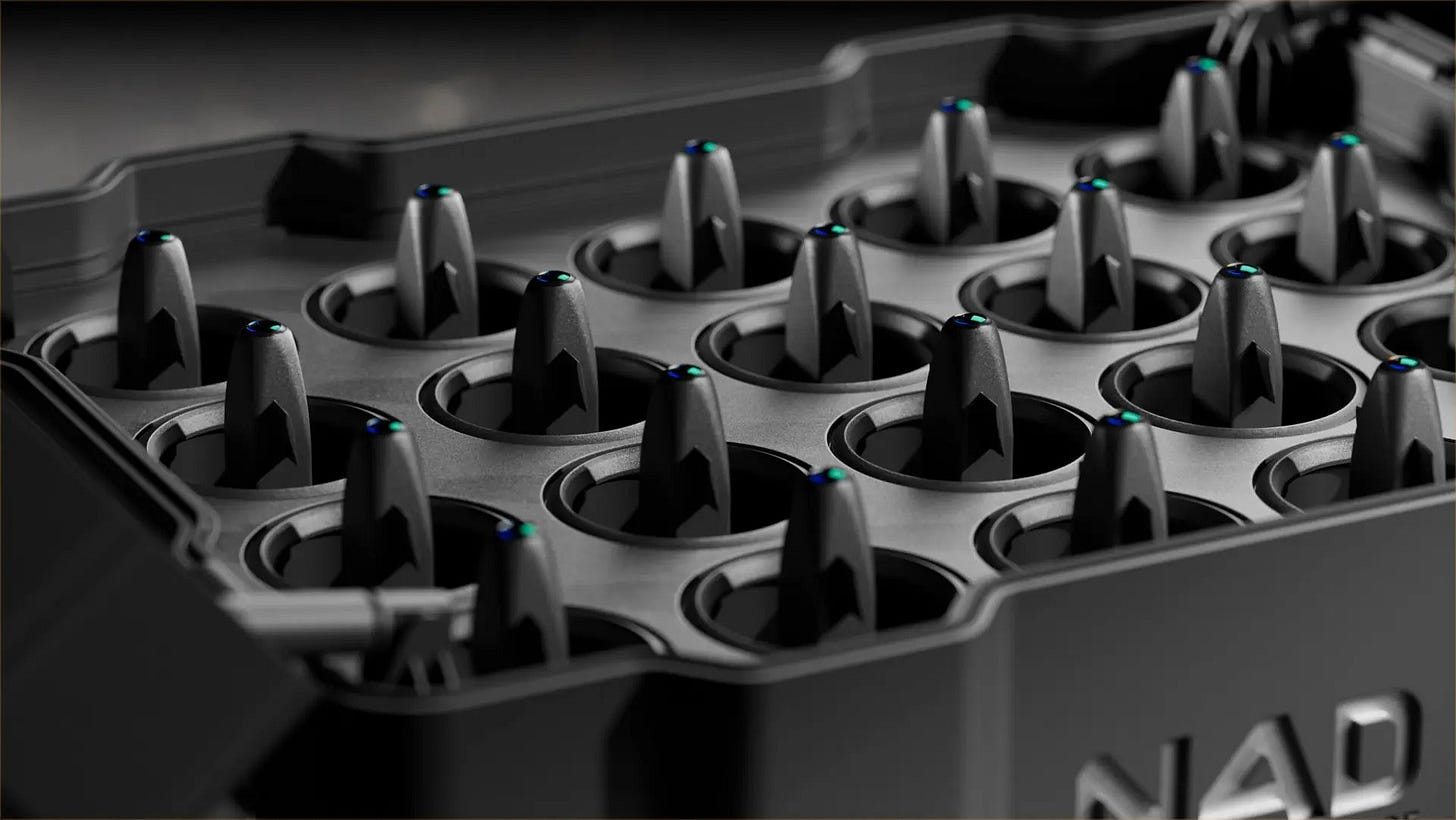

For the first time in modern air defense, militaries can think in terms of saturation rather than scarcity. With a projected cost an order of magnitude lower than traditional systems, planners can saturate entire sectors, critical infrastructure sites, or even convoy routes with mobile anti-drone bubbles that are disposable, relocatable, and endlessly scalable.

Let’s be blunt: most NATO countries don’t have the industrial base, or political appetite, to build $100,000 interceptors by the hundreds.

But they might build thousands of €10,000 autonomous interceptors without blinking. That’s what makes the Kreuger 100 tactically transformational. You don’t need a one-to-one kill ratio. You need enough coverage to overwhelm the swarm.

This changes the math of drone warfare entirely. Imagine an oil refinery, a bridge, or a radar installation shielded not by a multi-million-euro surface-to-air missile system, but by 20 or 30 Kreugers parked in underground tubes, mounted on Humvees, or scattered like landmines across the surrounding terrain.

Suddenly, that facility becomes a porcupine, too risky for even the most brazen drone operator to touch. The cost of attack starts to exceed the cost of defense—not the other way around.

Even more compelling is what this means for maneuver warfare. The Kreuger 100 isn’t tethered to a command bunker or a centralized fire-control system. It can be deployed on the move, launched from the back of a pickup truck, an infantry fighting vehicle, or even by dismounted troops operating in drone-infested areas. Ukrainian forces operating in contested zones like Kupyansk or Kherson could carry Kreugers into the field the same way they once carried RPGs.

In this way, the Kreuger 100 turns every battalion into a self-contained air defense node.

And that creates headaches for adversaries who rely on drone reconnaissance and loitering munitions to shape the battlespace. A mass-deployed, software-updated drone interceptor breaks the kill chain before it starts: silencing spotters, blinding artillery, and forcing enemy commanders to think twice before flying anything beyond the front line.

Mass deployment also creates redundancy. In traditional air defense, if you lose one system, you lose the entire bubble. But with Kreugers, redundancy is built in.

Shoot down five? There are 50 more. Hack one? The next software patch locks you out. Each individual Kreuger might be expendable, but the architecture as a whole is resilient, agile, and self-healing.

This is a strategic mindset shift: from exquisite and irreplaceable to modular and many. It’s the difference between defending the sky with Fabergé eggs or with machine-cut marbles—cheap, countless, and deadly in numbers.

And that’s why Kreuger 100 isn’t just a counter-drone platform. It’s a doctrine, and one designed to win in a world where the enemy has more drones than you have bullets.

European Autonomy

NAD founder Karl Rosander is blunt: Europe has a defense problem, and it's wearing a "Made in America" label.

The Kreuger 100 isn’t just a weapon, it's a declaration of intent. After US Vice President JD “Smokey Eyes” Vance told European leaders not to count on Washington for continued defense support, Rosander and company doubled down on the idea that Europe must build its own arsenal. The timing couldn’t be better.

Unlike traditional primes, NAD moves fast. Its team comes from tech, not just defense—ex-Palantir, FOI, Kratos, Saab, and even Spotify. This cross-pollination means they're solving battlefield problems like a startup, not a government contractor.

Also, bringing cross-functional experts together from these seemingly disparate companies creates what I like to call “planned serendipity.” In that environment, ideas manifest more frequently, building on the diverse backgrounds of the team. In other words, NAD is engineering its own good luck.

Rosander has also called out ESG investment rules that currently limit venture capital into defense startups. His argument? If public-private collaboration could produce a COVID-19 vaccine in under a year, there’s no reason defense innovation can’t move just as fast.

The real bottleneck, he says, is bureaucracy and perception.

NAD isn’t content to just stop drones over Donetsk. The Kreuger 100 is dual-use by design. That means the same tech can be used to protect airports, nuclear plants, government buildings, and ports. With drone incursions on the rise across Sweden, including surveillance drones over critical infrastructure, the domestic application is obvious.

But in Ukraine, or anywhere that drone warfare is becoming the norm, the Kreuger 100’s modular, scalable, and software-defined approach offers a rare edge. A smart bomb might cost six figures. A smart drone interceptor might cost thousands, and with software updates, it only gets smarter over time.

That’s not just innovation. That’s survival.

The Kreuger 100 is proof that the next revolution in air defense won’t be led by $100 million missile systems or billion-dollar contracts. It’ll be built in garages, tested in forests, launched by hand, and guided by software. And if it can knock down a $50,000 kamikaze drone with a $5,000 battery-powered interceptor?

Well, that’s not just cost-effective. That’s a paradigm shift.

That’s it for today, friends. Subscribing is the single best way to support independent journalism. Please consider a free or paid subscription so I can keep up this crazy writing tempo.

And as always, Crimea is Ukraine.

Слава Україні!

A Putin supporter left a comment saying my writing is “clearly an advertisement from the manufacturer” and that “AI could do a better job.” I considered responding to the prick but opted for the indefinite ban. In case he makes his way back, убирайся из Украины, придурок.

The US is unreliable in trade and defense. Glad to see Europe marching ahead.